Get this article and more at my Patreon months before they arrive on my website. Exclusive short stories and novel chapters are only available via a Patreon subscription.

Used to great effect by Shakespeare in the 16th century, the five-act structure was later analyzed by German playwright Gustav Freytag in 1863 in his book, Die Technik des Dramas. It has since been used for books, movies, and television into the modern day. While more complex theories of story telling have emerged, they can all be overlayed with the five-act structure in the same manner as most stories can be broken down into the three-act structure.

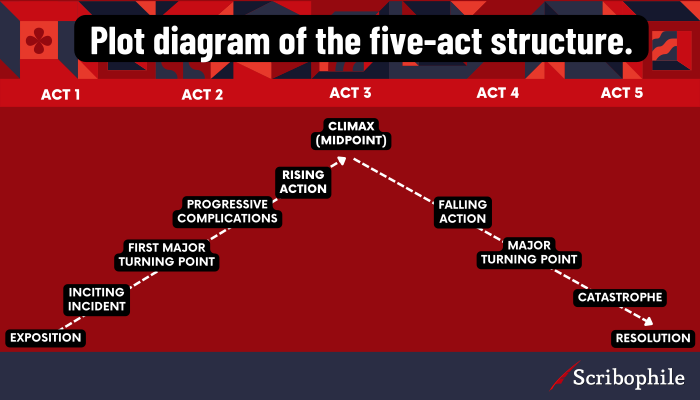

Seen in the graphic above, there are many aspects to the structure beyond merely a simple five acts. Same as the three-act structure, there are points within each act that drive the narrative toward the moment we shift the reader into the proceeding act.

The main acts consist of Exposition, Rising Action, Climax, Falling Action, and Resolution (or also know as the Denouement). Each section serves a specific purpose within the story and while one can look at a Shakespearean play and mark the five acts as generally equal in length, that will not always be the case for every story.

This blueprint will become incredibly important as we move forward the discuss both the Hero’s Journey and Save the Cat, both popular frameworks for today’s writers of books, shows, and movies.

Throughout this article, I will be referencing a show called Babylon 5 created by J. Michael Straczynski. Beyond my love for the show itself, it is a textbook example of how the five-act structure works in both a micro level (within each episode) and a macro level (over the course of it’s five seasons). Each season demonstrates one of the acts when the viewer takes in the larger story. I’ll do my best to avoid spoilers for those who haven’t watched it, but you should. Though dated, it’s still phenomenal and available on streaming, though the exact platform is constantly changing.

EXPOSITION

This is where you set up your story. Here you introduce main characters, create your inciting incident, establish voice, build your setting, and maybe even tease your villain or villains. Many of these were discussed in Part 1 – Three-Act Structure. In Babylon 5, the first season sets up several of the mysteries that will evolve into larger revelations down the line. We meet our principle characters, minor antagonists, and eagle-eyed viewers will catch glimpses of things to come. Subtle foreshadowing can be a boon to your writing if well deployed in the exposition, but don’t info dump. One of the worst pitfalls within the exposition phase is the possibility of taking pages to tell the reader about the world rather than show them.

Yes, that old adage and super annoying thing teachers will say and never truly define. Show don’t tell. For now, I’ll give you a quick glimpse.

She was happy. VS A smile spread across her face.

One tells us her feelings, the other infers them.

As for doing this for setting:

It was a cruel world. VS Screams and taunts of both victim and assailant rang through the night. No one bothered to glance up from their business to attend the near constant music of a city on the edge of collapse.

Inference is key. Telling details are any story’s best friends.

Another great example is the opening line of William Gibson’s Neuromancer. I don’t have permission to reproduce it here. It’s one of the most famous opening lines of a cyberpunk novel ever written. You can read it here.

The exposition will always close out on a plot point or, as labeled on the graphic, the first turning point. Plot points were also discussed in Part 1.

You’ll notice on the graphic that we have progressive complications and rising action next. Even though progressive complications come first while Act 2 is often referenced as the Rising Action, they are both part of the same section.

Our Act 1 ending plot point will set our story off into an unexpected direction which in turn sets off a domino effect of complications. We don’t want to overwhelm both our reader and protagonist, so these obstacles will start small and grow in severity as they avoid, battle through, or get run over by and survive each one.

RISING ACTION

At the end of Season One of Babylon 5, our heroes face a life and world altering catastrophe. The next season begins with one hero mysteriously gone, a new, untested one arrives, political intrigues are multiplying, and insidious forces creep in from all sides. Season Two starts with several new arrivals who must prove themselves. They are faced with small tests which transform and grow in importance as the story progresses. This is the rising action and progressive complications working hand in hand. Just as the graphic shows the line going up hill, imagine you are rolling a small snowball up that snowy hill. By the time you hit the top, you will likely have a sizable boulder.

Often there will be another large event or revelation that pushes us up those last few steps to get to the next act. Again, this moment will change the trajectory of the lives of your characters. Often, they will be forced to make the first of many consequential choices.

The rising action is nearly always defined by the main characters reacting to events around them. Their choices are almost reflexive rather than considered. Once the second plot point hits, our characters face a moment of truth where they need to regain their agency if they hope to survive. This won’t happen all at once, however. It’ll occur over the course of Act 3, the climax.

CLIMAX

We’ve reached the top of the mountain with our enormous ball of snow. The problem is we need to get the ball of snow down the hill without killing everyone below. We have to guide our creation towards the edge and have the protagonists make some important decisions. Here is where your hero will gradually reclaim their agency.

Throughout the third season of Babylon 5, our heroes are forced to take ever greater risks, avoid more dangerous traps, and ultimately make several choices that will both set their worlds to chaos and reclaim the freedom they need to succeed in their future battles. They know the boulder has to go over the hill, but they begin to make choices they hope will allow them to control the descent and save as many as possible. Throughout this act of your story, tensions are high and the choices made will define everything that follows. At the end of this act, you will try to ease the boulder over the edge of the mountain, but no matter how well your heroes have planned, every terrain, especial one full of uncertainty, hides unpredictable complications. Just because we left the Rising Action behind doesn’t mean we abandoned our progressive complications. Where would the fun be in that? After all, the villains weren’t sitting around waiting for the heroes to make a move. Conflict isn’t chess. No one gets to take turns.

FALLING ACTION

Act Four is going to be fast-paced and full of action. This can be take the form of physical, emotional, and/or spiritual action. Our protagonists have made their plans, but as any soldier will tell you, no plan survives the battlefield. Things happen and plans change. Your heroes went into battle with a plan, but so did the villain. Don’t forget, they never sacrificed their agency and have been plotting and moving their pieces around the board all the while the heroes were figuring themselves out.

At the end of Season Three of Babylon 5, we learn a great deal about the looming threat of the series, its goals and plans. In fact, we learn a lot about a lot. These revelations and season finale turning point lead our heroes toward a different understanding of the battle raging around them and the ones still to come. On the graphic, this is labeled as the second turning point. Again, I’m going to push back a little on that as that moment lines up with the end of Act 3. Because of this turning point, the Falling Action of Season Four sees an overall change in how the battle is fought by all sides. The heroes enter with a better understanding of the overall situation, but the face of the conflict changes in a way no one expected. This leads to our catastrophe. Regardless of the change, the story keeps barreling forward toward the inevitable final decisive confrontation.

This is our opportunity to wrap up all the major conflicts we’ve built throughout the story. After our catastrophe moment, the heroes will generally enter a phase known as “The Dark Night of the Soul,” which leads into “Gathering the Team.” The first phase is used in both The Hero’s Journey and Save the Cat Method while the second is only found in Save The Cat. We’ll go into these two moments in later articles, for now, a quick description.

Our heroes will have a moment of doubt. They will see their carefully laid plans blown apart. The snowball has escaped our control and everyone below is in danger. Everyone feels lost and hopeless. (The Dark Night of the Soul). However, this is where they regroup, make a new plan, and start again. In other words, they Gather the Team. From here they take the battle to the villains and succeed even though it seems impossible to overcome forces well beyond their capabilities.

At the end of Season 4 of Babylon 5 the good guys have won! They’ve saved, mostly, everyone.

RESOLUTION/DENOUEMENT

Earlier, I mentioned that Gustav Freytag wrote a book about the Five-Act Structure. Despite the term “denouement” being commonly in use at the time, first appearing in 1752, he referred to the fifth act as “Catastrophe.” He argued that this moment should be were the hero meets his inevitable destruction. In the Hero’s Journey, this would come under Sacrifice. Going forward, we will discuss Act 5 as the Resolution or Denouement which is the more common term in today’s craft theory.

As children, we read or were told fairy tales that became Disney movies. The one thing all these stories had in common was, “And they lived happily ever after.” For a long time, that single line was the resolution of the story. However, many writers have found that a story can be more satisfying if you show (there’s that word again) the happily ever after. Of course, one can argue that the resolution of Snow White is when the Prince Charming kisses the poisoned Snow White to wake her up, however, I would argue this is the final turning point of Act 4. There is certainly an argument to be made either way.

An interesting point about Babylon 5 here. The final, aired, episode of Season 4 was not the intended final episode of the season. At the time, the show was on the cusp of cancellation and they didn’t know if they would get a final season, so they shot a series finale. When they got renewed for a final, fifth season, that finale was shelved for later and they put together a kind of anthology episode. This is one of my favorite episodes because it shows what happens thousands of years into the future. Quick glimpses of humanities successes and failures, most echoing our shared past. It’s a clever way to shoot an episode on short notice and provide the audience with a glimpse into a fully-conceived universe.

The fifth season of the show takes us through all the aftermath of the numerous final battles. As we all know from history, just because a war ends doesn’t mean everyone is content or willing to leave their grievances in the past. People hold onto grudges, lives need to be rebuilt, and peace is sometime harder to hold together than uniting people under the threat of annihilation. The same is true of your story.

When the dust settles, how will your characters pick up the pieces and move on with their lives? Remember, your characters had a life before the book started and it will go on after the last page; unless they die. Show how they are going to pick up the pieces and move on. How has the course of events they’ve fought through changed them? Even when you win a battle, there is still the trauma of having fought it in the first place. Respect that and give it the attention it deserves.

You’ve reached the end. Once again, you have a foundation to build your work on. Or use it as an architecture to see if your story hits beats outlines above. If it doesn’t, look hard at those moments to be sure before you change anything. Sometimes, the beats present in metaphorical ways. If you still can’t find them, rework the story. Maybe that missed beat is a missed opportunity.

This framework will allow for more dynamic, complex stories than the three-act structure will on its own and help prevent you from rambling off into the ether to loose the focus of the story. Complexity is great as long as you don’t confuse the reader. Make sure the complexity is driving the story and main characters forward.

Now go forth and tell your story!