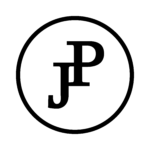

My hope is to not only convey everything I know and have learned about writing through this series of articles, but to help myself better understand the principles I’ll be discussing. There is an educational theory known at “The Cone of Experience,” or “The Learning Pyramid,” by Edgar Dale. It’s as follows:

To get started, let’s start with the macro aspects of writing and work our way, over time, down to the micro.

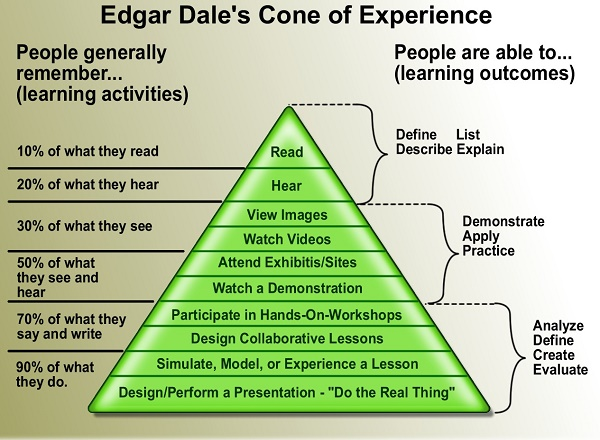

Whether a plotter or a pantser, we all need to understand that basics of story structure. This comes in many forms, but remember we are starting macro. Therefore, let’s look at the very basic concept of the three act structure; beginning, middle, end.

Ignore all the details, for now. We’ll come back to those in another installment.

The important bits right now are the beginning (setup), middle (confrontation), and end (resolution). Without these three basic elements of a story, your tale will not make sense or will be unsatisfying to the reader. Each of these three sections are transitioned with the use of a plot point. This is when a catalyst is introduced into the story to send it off into an entirely different direction, e.g. “You’re a wizard, Harry!” Or “No, I am your father,” (which doubles as a twist in the overall arc of the Star Wars Trilogy. We’ll get to twists later).

In the setup, we introduce our characters and tip over the first domino that will send our main character on their path. This is your opportunity to grab the reader with a tight hook, an intriguing Inciting Incident, a flawed hero, and interesting villain. All of these will be discussed in detail in later installments.

The middle of the book, the longest of the three acts in most cases, we have our larger confrontation. This section includes all the really fun stuff. You’ll have obstacles for the main character, wins and loses for both the hero and villain (more loses or near escapes for the hero), the big twist that knocks the reader and the hero on their rear, conflicting emotions, and wavering alliances. This is the meat of the story and where we keep the reader flipping pages. Once you’ve hooked the reader with the setup, you need to deliver on your promises to them in the middle. There is a great piece of advice that Dave Chappelle passed along to Will Smith in the show Bucket List when Smith was gearing up to try stand-up comedy. “You don’t have to be funny all the time, but you do have to be interesting all the time.” This is also true of the middle section of your story. You don’t have to be exciting all the time, but you do need to be interesting.

As we wind the story down in the resolution, our goal is to offer one, final, definitive confrontation that settles all the major issues of the various parties. Some smaller threads can and will be tied up before or after the last battle, but we need to have the one final moment that brings everything together and forces a satisfying end to the main conflict of our story. The biggest thing to avoid in this part of the story is to rush the ending. Too many times I’ve read grand sweeping tales that get to the end and rush to wrap it all up. Take your time. Bask in all that you’ve accomplished. Give your reader an ending worthy of the build-up in the middle.

Next up, we’ll expand our examination of story structure with the five act structure. As we delve into more complex principles, you’ll begin to see similarities and carry-overs. This will reinforce the idea that every story is subject to these foundational concepts. Even the most artistic, experimental piece builds on a foundation or it would crumble under its own weight. If you’ve never read an experimental story, I assure you, there is a metric ton of weight bearing down on those gravity defying tales. Without a strong foundation, they would be cast aside rather than lauded by readers and critics alike.

Finally, we need to go over plot points. These are the transitional moments between acts. In a stage play or television show, this is where they cut the scene after a surprising revelation. This isn’t the big twist in the middle. We’ll get to that. This is a moment, phrase, or discovery that sends the story off in an entirely new and often surprising direction. It won’t change the genre or tone of the story, only the focus. It can be foreshadowed, but until it is expressly declared via dialogue or prose, it isn’t a plot point. In Harry Potter, we see Harry use magic and we see the invitations to Howarts flooding the Dursley’s home, but until Hagrid shows up and says, “You’re a wizard,” the story doesn’t change direction. It’s that moment that sets Harry off towards Diagon Alley and Platform 9 3\4. In Star Wars, Luke finds Obi-Wan, learns about the Jedi and the Force, discusses the Empire, and even wants to help the princess; but it’s only after they discover the Empire has come and burned his family and home to the ground does he abandon his past life to enter into a new one.

A plot point doesn’t necessarily force the main character to abandon their comfortable life, but it does force them into unknown territory more often than not. They are now required to face the dangers they would normally have been oblivious to had they just shoved their heads under their pillows. It’s a character’s transitional moment. The first two examples are of an Act One to Act Two plot point. An Act Two to Three plot point is a transition that occurs after a major setback and will lead to resolving the primary conflict. This is something akin to Harry Potter discovering Dumbledore was sent away to the Ministry of Magic on the night they suspect Snape is searching for the Philosopher’s (Sorcerer’s) Stone. He decides to take matters into his own hands and changes the direction of the story, sending our three heroes to risk getting their house in further trouble and putting Harry of a collision course towards his first confrontation with Voldemort.

The twist is slightly different. The twist isn’t going to send your story in a different direction as much as it will change the reader’s and main character’s perspective of the stakes. A common example is when the main character thinks the threat is only to themselves but a twist shows them that the whole city is at risk or they were set up to fail. Enemies become allies. The hostages were switched and who you meant to save dies.

A rough comparison would be that the plot point is a cliff hanger while the twist is a shock that changes everything you thought was true.

Now go forth and write yourself a short story or outline using the three act structure. Or go ahead and use it to map out a favorite story or one you’ve written. Test these things out for yourself and learn.

And remember to have fun.

Get this article and more at my Patreon months before they arrive on my website. Exclusive short stories and novel chapters are only available via a Patreon subscription.